TED (Technology, Education, Design) has as its tagline "Ideas Worth Spreading." It started in 1984 and now broadcasts talks by world renowned speakers on diverse topics. TED features two annual conferences, the TEDTalks video site, TED fellowships, and the annual TED Prize.

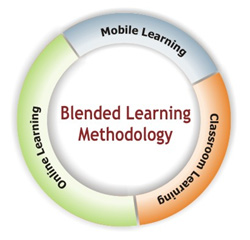

TED (Technology, Education, Design) has as its tagline "Ideas Worth Spreading." It started in 1984 and now broadcasts talks by world renowned speakers on diverse topics. TED features two annual conferences, the TEDTalks video site, TED fellowships, and the annual TED Prize.Learn Out Loud is an audio book and podcast site devoted to languages, literature, philosophy, politics, religion, science, technology, and travel, among others topics. Most of the content comes with a cost, but its ever-expanding database of free readings, lectures, webcasts, and webinars are worth downloading onto your smartphone or listening to by streaming. Several of these are semester length for those seeking in-depth content.

Academic Earth contains courses and lectures by professors from Berkeley, Columbia, Harvard, MIT, Princeton, Stanford, Yale, and other major universities on virtually every major subject area you're likely to find in higher education. Some recent topics: literary theory, stock market simulation, the development of thought, and Paul's ministry.

Academic Earth contains courses and lectures by professors from Berkeley, Columbia, Harvard, MIT, Princeton, Stanford, Yale, and other major universities on virtually every major subject area you're likely to find in higher education. Some recent topics: literary theory, stock market simulation, the development of thought, and Paul's ministry.  Do Lectures founded in 2005 by David & Clare Hieatt and based in Wales, has as it premise, in its own words, "people who Do things can inspire the rest of us to go and Do things, too. So each year we invite a set of people down here to come and tell us what they Do. They can be small Do’s or big Do’s or just extraordinary Do’s. But when you listen to their stories, they light a fire in your belly to go and Do your thing, your passion, the thing that sits in the back of your head each day, just waiting, and waiting for you to follow your heart."

Do Lectures founded in 2005 by David & Clare Hieatt and based in Wales, has as it premise, in its own words, "people who Do things can inspire the rest of us to go and Do things, too. So each year we invite a set of people down here to come and tell us what they Do. They can be small Do’s or big Do’s or just extraordinary Do’s. But when you listen to their stories, they light a fire in your belly to go and Do your thing, your passion, the thing that sits in the back of your head each day, just waiting, and waiting for you to follow your heart."