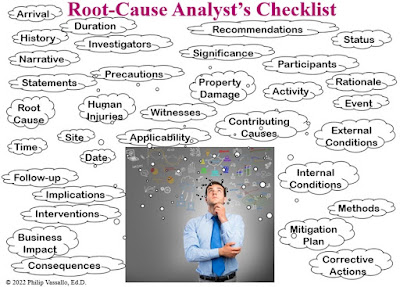

In this series on report writing, I have often looked at the contents that make up reports. (You can look at any of the links listed at the end of this post.) I won't discuss the contents of the root-cause report since I can think of 33 elements, as the image shows. You would better spend your time here reading more about strategy than about contents because cause causes all kinds of problems. Get it?

1. Overcome confirmation bias. We all tend to fall into confirmation bias, the tendency to misinterpret evidence as confirmation of preestablished beliefs. Let's look at three claims where confirmation bias plays a major role.

First, we'll start with the claim Most people voted for the challenger because they were fed up with the incumbent. Many other reasons are possible, including economic issues beyond the incumbent's control, an appealing message from the challenger, and higher-than-usual voter turnout comprising a new demographic, to mention just three. Yet we find it easy to accept the claim without analyzing the exit polling data because we believed the assertion all along.

Second, People with advanced degrees will earn more money in this economy. This assertion seems reasonable on the surface, as studies over a half-century have shown a strong link among education, occupation, and income. So why argue with a long-held belief based on apparently indisputable data? Because the economy is changing dramatically with so many people working from home on their computer, where a blend of creative and technological talent trumps most everything else. So while the premise may be true, it also may not be. We would want to research the situation further.

For the third example, Human error caused the operator to be injured when a shard of a shattered lab bottle she dropped while walking across the production floor cut an artery on her ankle. We seem to have a clear-cut case here, but too many other factors are at play. Why was she not wearing protective footwear? Why were the lab bottles stored so far from the operator that she had to walk across the production floor to retrieve them? Why didn't a material handler feed her the bottles at her workstation? Was she rushing under direction of her supervisor? Was she fatigued from working too many consecutive hours? Was she confronted with a tripping hazard beyond her control? You might say that none of these answers changed the cause of human error, but they surely can contribute to the cause—and one or more may be the root cause.

So how do we overcome the complacency of confirmation bias? We can start by not trusting ourselves. We should be suspicious of our experience, knowledge, and viewpoints. Then we should seek multiple and divergent sources that challenge our assumptions, accepting conflicting evidence that makes us look deeper into the event. This mindset leads to the next tip.

2. Use a fishbone diagram. The fishbone diagram, also known as the Ishikawa diagram after its creator, Kaoru Ishikawa, compels us to look at the total picture (see illustration). By considering management, we now see causes like the operator being rushed by her supervisor, or her being allowed to work while fatigued. Looking at personnel, we detect her not wearing proper protective equipment (although we can point this issue to management or equipment as well). The process is to blame when considering the distance she had to walk or the lack of a trained material handler on site. A tripping hazard could be attributable to the environment.3. Ask the 5 Whys—and sometimes more than five. The 5 Whys is a repetitive process for determining the root cause of an event. The idea is to ask why after getting an answer to the previous why. Of course, sometimes asking why even five times is not enough. Let's see how many whys we need to ask about the operator who was injured to get some closure on the case.

1. Why was the operator injured? A shard of a shattered lab bottle slashed her ankle.

2. Why was her ankle slashed? It was exposed.

3. Why was her ankle exposed? She was not wearing proper protective footwear.

4. Why was she not wearing proper protective footwear? She left it in her locker.

5. Why did she leave her proper protective footwear in her locker? She said she doesn't need to wear it.

6. Why doesn't she need to wear proper protective footwear? Her supervisor does not enforce the policy.

7. Why doesn't her supervisor enforce the policy? He said management allows him flexibility in enforcing the policy.

While asking the 5 Whys, beware of beside-the-point questions, such as Why does management allow the supervisor flexibility?, as there is no excuse for not adhering to the policy. Also, follow on-point questions, such as Why were the lab bottles stored so far from the operator that she had to walk across the production floor to retrieve them?, as this discovery may lead to a new preventive measure.

Other reports in this series: