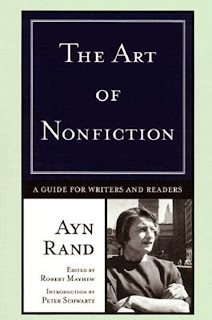

Developing writers and interested biographers should listen

carefully when a celebrated author is talking about writing, and Ayn Rand’s The

Art of Nonfiction is no exception. Talking

about writing is the operative phrase here, as this book is actually a

collection of recorded lectures from a course Rand led for friends and

associates in 1969. But readers should not feel cheated. At age 64, Rand had written

much, including all four of her novels, two of them, Atlas

Shrugged and The

Fountainhead, ranking at numbers 1 and 2 on the Reader’s List of 100

Best Novels of the Modern Library.

She also created a dozen nonfiction books and essay collections, many plays and

screenplays, and her own philosophical system, objectivism, which

figures prominently in all her work. In any context, her ideas on the creative

process are well worth a listen.

The wisdom Rand gained from her writing experience is unique,

and she evokes it engagingly. She begins with an encouraging premise: “Contrary

to all schools of art and esthetics, writing is something one can learn. There

is no mystery about it.” Her walk through the writing process may seem to take

a traditional route at first glance, as she divides her topics among the usual chapters

of creating an outline, writing the draft, and editing. Along the way, however,

appears her uncompromising worldview. How else would a chapter “Applying

Philosophy Without Preaching It” show up in such a discussion?

Rand’s objectivist inclinations are unmistakable in virtually

every utterance. She says, “Writing is an unpredictable process; it does not

proceed regularly at so many words per minute.” With this mindset, she tackles moments

in the writing process in her singular way: “There are two separate jobs: the

job of thinking and the job of expressing your thoughts. And they cannot be

done together. If you try, it will take you much longer, and be much more

painful.” She sees writing the first draft as a subconscious activity

and editing as a conscious one, requiring “a switch to … a different mental set.”

Far from remaining on a purely philosophical plane, she systematically

explains how her method works. Her chapter on editing tenders several practical

tips, and her outlook on style is refreshing. “The first thing to remember

about style is to forget it,” she writes, accepting that style is so difficult

to learn and teach. This realization does not prevent her from dedicating a

40-page chapter to a discussion on how it emerges in several published passages.

Authors who contend with writer’s block can benefit from adopting

Rand’s viewpoint. She uses an interesting term to describe it: the squirms. Embracing

the squirms as a necessary part of any creative process, she implies that they

are not a cause to give up writing but to understand and exploit what’s driving

them at the service of the manuscript. And she practiced what she preached,

rarely diverting herself from the composing task at hand: “When I was writing Atlas Shrugged, I accepted neither day

nor evening appointments with rare exceptions, for roughly thirteen years. “

Understandably, readers might be put off by two problems in

this book. Rand frequently references fiction to describe the task of an

essayist, even though she sees significant differences between the two genres. Also,

she constantly returns to her own fiction to illustrate examples of excellent

writing during her talks.

In Rand’s defense, during these lectures she was speaking to

devotees, who benefited from references to her familiar prose. In addition, she

did not intend to see these lectures in print. Even if she did, she had no hand

in their print version, as it was edited by Robert Mayhew and published in 2001,

nearly two decades after her death. Being above all else a logical and practical

thinker, Rand likely would have changed some the illustrative texts to reach a

wider audience if she wrote it herself.

Nevertheless, the presence of her narrative passages does the

book no harm. In fact, Rand fans will enjoy the autobiographical aspects of the

book. For instance, she admits to being weak at titling books, crediting her husband

Frank O’Connor for coining the title Atlas

Shrugged (She wanted to call it The

Strike.)

Those who are likely to pick up such a book will not be

disappointed. A lot of gems are to be found within the 192 pages of The Art of Nonfiction.