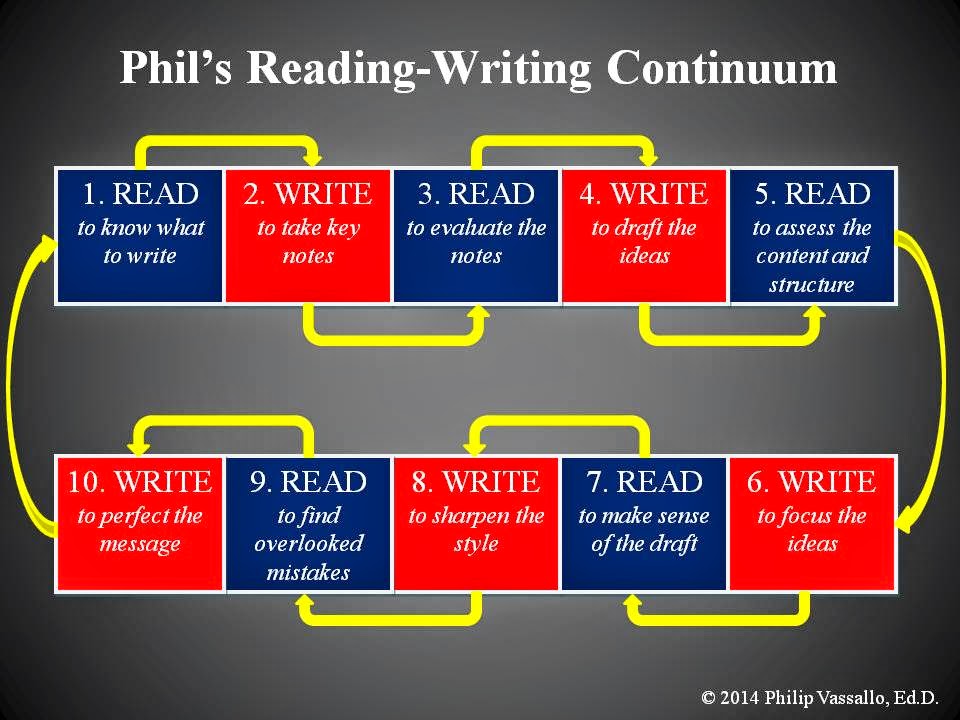

Working from the organized list of ideas that you created in Steps 2 and 3, you are ready for Step 4, write to draft the ideas. When referring to a rough draft, I think of riding in an SUV, (speed, uniformity, volume). Here is what I mean:

- Speed – Good writing requires rewriting, so the sooner you complete a rough draft, the more time you will have to improve the quality of the message.

- Uniformity – You will not be drafting blindly since you will be using your structured idea list, so you should find sticking to your plan easy.

- Volume – In a rough draft, quality is not half as important as quantity. The more you write, the more you can assess.